July 12, 2016

by John A. Kelley, III, published by Hotel News Now

Some state fiscal budgets have been heavily scrutinized over the past decade due to considerable deficits, forcing the state legislatures to reduce spending in areas that are considered more or less discretionary. While each state has its own funding model for tourism spending, many states and municipalities levy occupancy, admission or other tourism-related taxes on the sale of products and services to fund tourism budgets.

Taxes from the state’s general fund are not always the main source of revenue for its tourism budget. Rather, tourism tax revenues are sometimes redirected into the state’s general fund, which means those dollars are not being reinvested to help the industry that generated them. Reducing or redirecting tax dollars that support tourism efforts negatively affects the basic foundation on which tourism-related businesses rely: mass marketing, public resources, infrastructure, etc. A pertinent question that arises is how travel and tourism industry advocates can illustrate the economic benefits that the industry provides at the state level.

Consider the following 2015 statistics from the U.S. Travel Association regarding the economic impact from travel and tourism in the U.S.:

• Direct travel and tourism spending totaled $947.1 billion, which spurred an additional $1.2 trillion in indirect and induced spending for a total economic impact exceeding $2 trillion.

• U.S. travel and tourism supported 8.1 million jobs that earned an aggregate income of $231.6 billion in 2015.

• In 2015, $147.9 billion in federal, state and local tax receipts were generated from travel and tourism-related spending.

• Leisure travelers generated the most spending, nearly $651 billion, while business travel generated more than $296 billion.

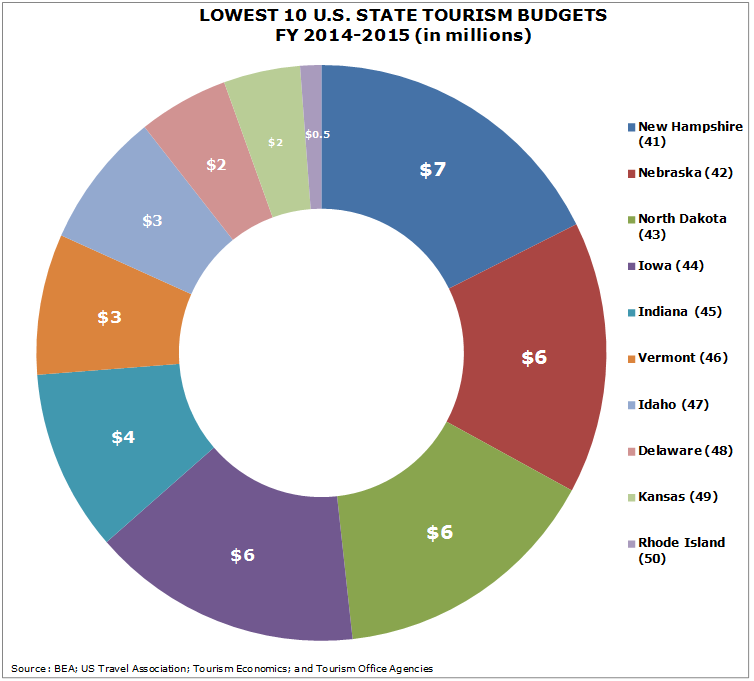

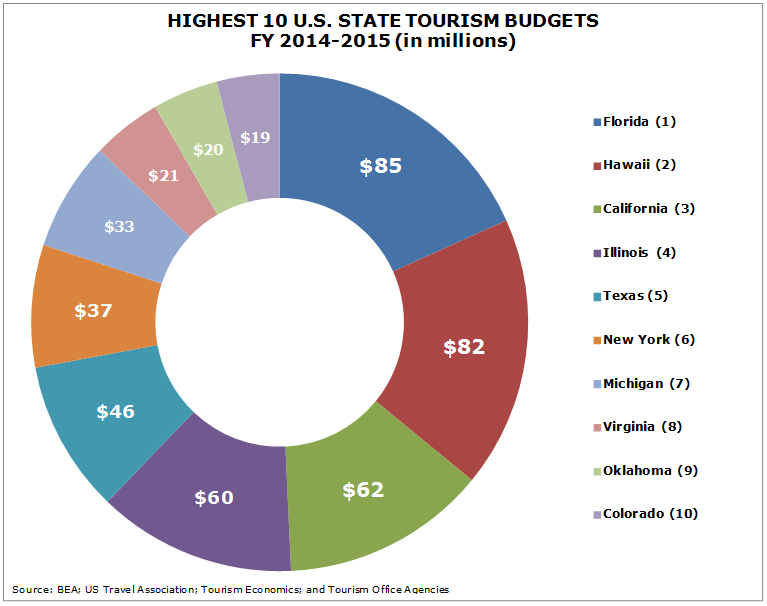

In this discussion, different states will be profiled and used for comparative analysis. The following graph presents the 10 highest- and lowest-funded state tourism budgets for FY 2014-2015, which will help illustrate the large differences between states.

Many states were near the average annual tourism budget of $17 million, but outliers exist on either end of the spectrum. For example, Washington’s state budget allocated no money annually toward tourism whereas Florida aggressively allocated $85 million. The significant disparity in tourism budgets can stem from state size, population, significance of the tourism industry, funding models, assessment of tourism-related taxes and budget constraints.

Many states were near the average annual tourism budget of $17 million, but outliers exist on either end of the spectrum. For example, Washington’s state budget allocated no money annually toward tourism whereas Florida aggressively allocated $85 million. The significant disparity in tourism budgets can stem from state size, population, significance of the tourism industry, funding models, assessment of tourism-related taxes and budget constraints.

Sarah Leonard, president and CEO of Alaska Travel Industry Association, explained in a phone interview that the tourism budget “faced a reduction from about $10.2 million to $4.5 million in fiscal year 2016-2017 in state funding as a result of the decrease in taxes generated from the sale of oil,” a commodity that has experienced a dramatic decline in price since 2014.

The remaining portion of ATIA’s budget is generated from other revenue sources, including membership dues, marketing contracts with the state and its annual convention. Leonard explained that she “will need to make do with the revised budget but hopes to secure a sustained funding model that provides a consistent level of funding” despite external economic forces.

Travelers to Alaska spent $1.9 billion in FY 2014-2015, which supported about 39,700 full- and part-time jobs and generated roughly $187.8 million in local and state tax revenues.

In 1993, the Colorado state legislature ceased funding for its tourism office and did not reinstate funding until 2000. During that period, it was reported Colorado’s tourism share decreased 30%, resulting in an annual $2 billion loss of state tax revenue. That loss was made up through further budget cuts or tax increases on residents and/or businesses. Seeing the ramifications, Colorado made a 180-degree shift, re-evaluating the importance of funding tourism. Colorado’s legislature earmarked roughly $14.7 million in funding for the state’s tourism office in 2012, and the benefits have been significant. In 2013 and 2014, an economic report by Dean Runyan Associates estimated every dollar invested from Colorado’s tourism office generated $344 per visitor spend, which resulted in a return of $25 in state and local taxes per tourism dollar invested.

More recently, the Washington legislature ceased state funding of the tourism office due to significant budget deficits, resulting in the office’s closure in June 2011. As a result, the Washington Tourism Alliance has operated on a privately funded budget of about $800,000 annually.

A common argument is there is not a huge need to invest in tourism since people will visit whether or not the state’s destinations and attractions are marketed. Additionally, some are skeptical as to whether a net return exists. Neither of these reasons considers the ever-changing landscape of tourism and the global economy.

Each year travel and tourism become more global thanks to advanced technology, proliferation of social media, and lower costs to travel domestically and internationally. As growth in the tourism industry outpaces growth in other sectors, including energy, it is critical that state governments re-evaluate the importance of this industry as an economic driver. Ignoring the importance of tourism and its economic benefits could put a state at a disadvantage on a national and global scale.

Understanding the need for a sustainable tourism budget

According to the World Travel and Tourism Council, two main tenets drive the need for tourism planning and marketing: the need to deliver a consistent message and increased competition between destinations. In essence, tourism marketing is branding a destination so it resonates with locals and potential visitors.

Competition is growing exponentially, and those states that actively invite travelers by showcasing their unique amenities and attractions will increase their market share and garner a larger portion of tax revenues from increased traveler spending that benefits residents and businesses alike. Resources provided to state tourism offices and how those resources are used will affect the effectiveness of that state’s marketing campaign and ability to connect with travelers who have more options than ever.

According to the U.S. Travel Association, tax revenue generated by travel and tourism reduces each U.S. household’s tax burden by $1,192 annually. This savings is a major economic benefit to constituents and underlines the importance of travel and tourism to the overall U.S. economy.

Illustrating travel and tourism’s ROI

As with any investment, you want to know if the return will be positive, neutral or negative. Many tourism offices commission an independent economic impact study that calculates the return per dollar invested, as well as other factors that benefit from tourism spending, such as tax revenues generated, employment and total economic impact.

Finding the right data to project the importance of implementing a sustained tourism budget can be difficult. Simply calculating metrics without comparing them to a benchmark can provide inaccurate conclusions.

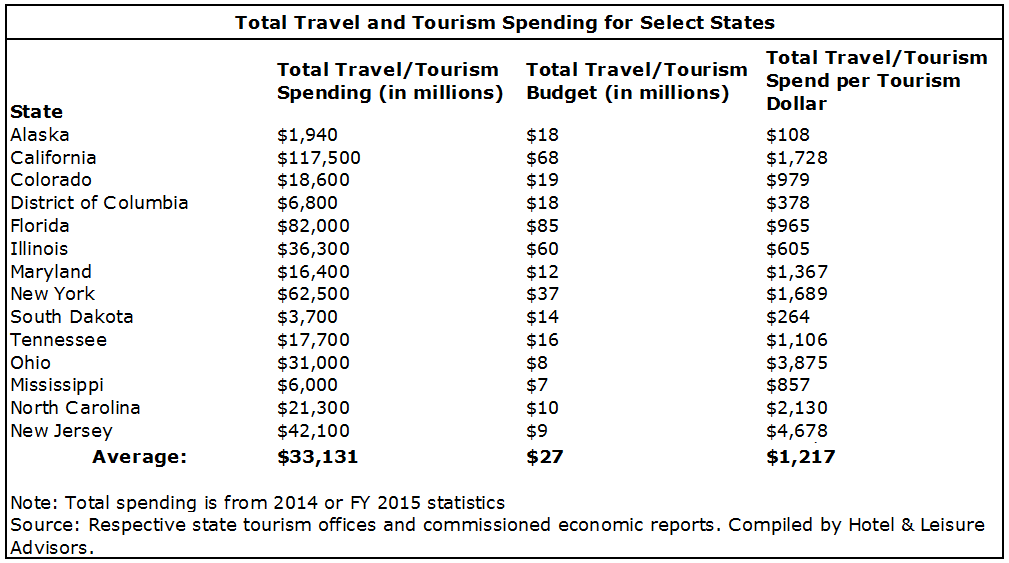

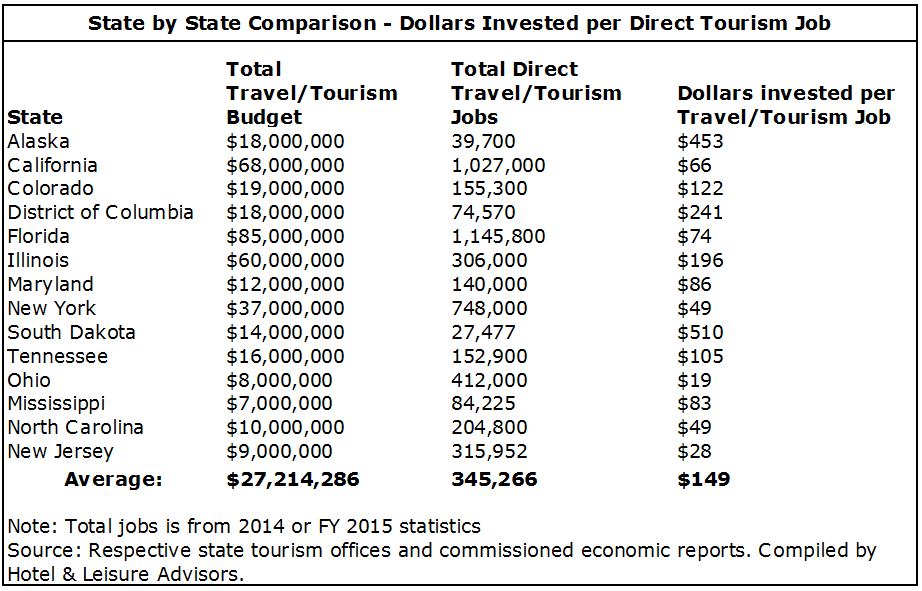

Consider the following table that shows total travel and tourism spending in select states and how it translates to total spending per tourism dollar invested:

These large numbers can be difficult to grasp at first sight, especially since we are discussing annual direct tourism spending in the billions of dollars compared to tourism budgets in the millions of dollars. This table is meant to show the wide range in total travel and tourism spending per tourism dollar invested.

This data can be found in some economic impact studies, but when compared to other states, it’s clear this metric does not provide much significance. Why? We must consider that travel and tourism spending encompasses a variety of expenditures, including but not limited to lodging, flights, rental cars, food and beverage, gasoline and entertainment.

The effectiveness of a state’s tourism budget should not be predicated on total spending since there are too many variants included in how total spending is calculated. This data might be more telling if compared to the respective state’s year-over-year figures.

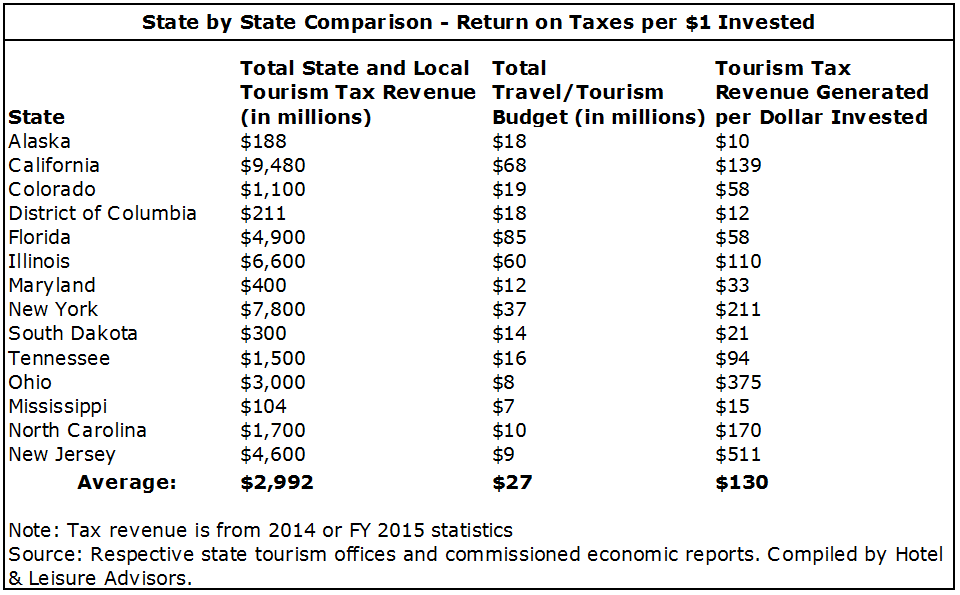

Another consideration that may be a better return on investment determinant is the return on combined state and local tax revenues generated, which is better than analyzing broad spending since each state has different attributes such as cost of living variances, higher concentration of destination cities, attractions, etc.

Each state allocates a different dollar amount of their overall tourism budget to marketing campaigns that use a variety of channels such as social media, billboards, magazine and television advertisements. This analysis considers total tourism budget spending, not just marketing dollars. While travel and tourism tax revenue as an independent variable might be more informative than using the aggregate travel and tourism spending as an independent variable, there is still a wide range in the sample.

The returns shown are affected by the different tax levies each state assesses. For example, California charges a tourism marketing tax on rental cars to specifically help fund the state’s tourism budget. Analyzing dollars spent specifically on tourism marketing and comparing that return to other states would generate more valuable data to analyze the effectiveness of a state’s tourism campaign.

Aside from analyzing return on investment from a monetary perspective, evaluating a tourism budget based on the number of jobs the industry supports can reveal pertinent information. The following table indicates the dollar amount invested per job directly produced by the travel and tourism industry.

The wide range is reduced in this analysis, which shows there is potentially more correlation between a tourism budget and direct jobs created. Alaska; Washington, D.C.; and South Dakota invest a disproportionate amount of tourism dollars per job, which skews the average. If we exclude these two states and D.C., the average investment per direct tourism job decreases to approximately $44.

This analysis illustrates how a state might value the tourism industry relative to other states. Overall, one out of nine jobs in the U.S. depends on travel and tourism, and the industry ranks seventh in terms of employment compared to other major private industry sectors, according to the U.S. Travel Association. It’s important for travel and tourism proponents to illustrate the importance of the industry and the economic weight it will carry into the future.

Comparing tourism performance with lodging demand

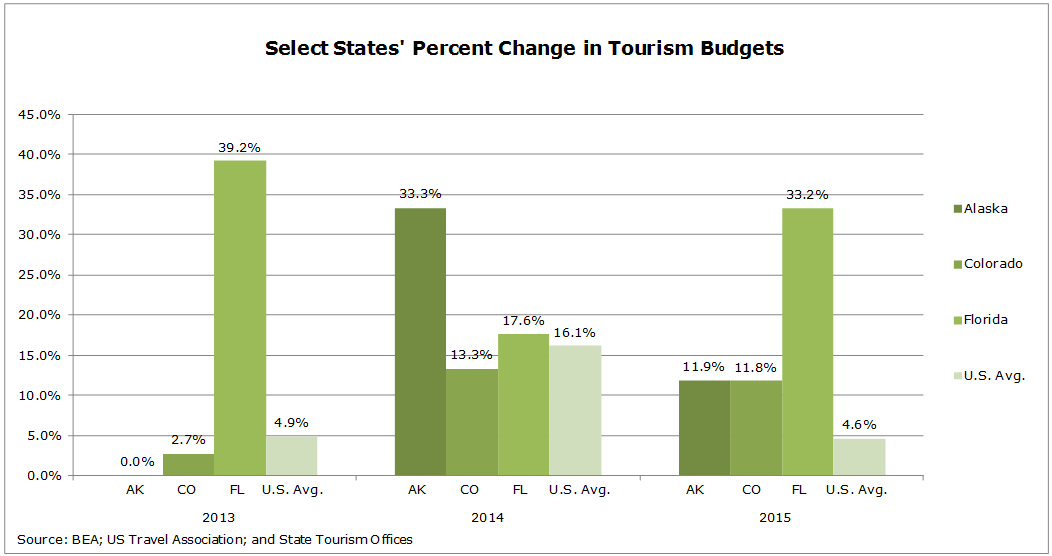

Another way to quantify and illustrate how state tourism budget dollars can positively affect the industry is by analyzing demand trends in a respective lodging tract such as a state or metropolitan statistical area. The following graph indicates the tourism budget percent changes over a three-year period in Florida, Colorado, Alaska and an average of U.S. states.

Florida’s tourism office, Visit Florida, reported record visitation of 105 million in 2015. The state’s legislature and Governor Rick Scott have been proponents for the industry, consistently increasing its tourism budget at rates above the U.S. average. In FY 2012, Florida allocated $38.8 million to tourism and over a four-year period increased it to $84.6 million.

Colorado has received similar championing from its state legislature and governor. Its tourism budget in FY 2012 was $14.6 million and reached an all-time high of $19 million in FY 2015. Governor John Hickenlooper has proposed increases in tourism spending each year and actively promoted the benefits the industry provides to the state.

Both of these states have instituted a sustainable funding model for their tourism offices to ensure they’re maintaining and/or increasing their share of the robust tourism industry.

Leonard explained Alaska competes more as an international destination due to its geographical location and unique characteristics. The state increased funding after the financial crisis in 2008, and it reached a high of $17.9 million in FY 2015, which consisted of state and private funds.

But the state legislature has not instituted a sustainable funding model, which has resulted in the total budget being reduced to $10.2 million in FY 2016. The $7.7 million reduction will limit the ATIA’s domestic and international marketing and outreach capabilities. The uncertainty of funding year to year makes it difficult to implement a comprehensive tourism strategy similar to that of Florida or Colorado.

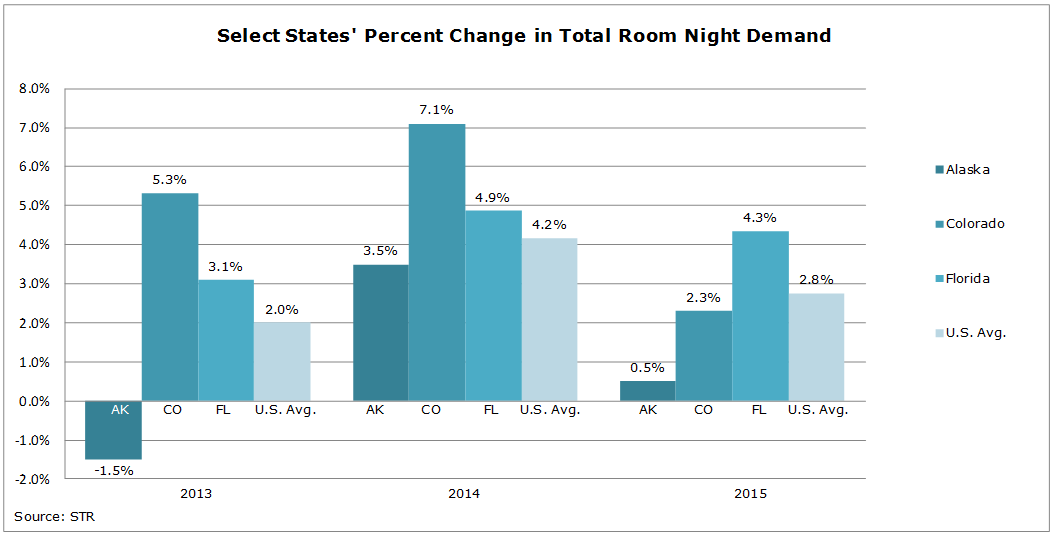

The following table shows the percent change in total room night demand for Florida, Colorado, Alaska and the average of U.S. states.

According to data from Hotel News Now’s parent company STR and other industry reports, the hotel industry has achieved record year-over-year increases in demand over the past several years. This can be attributed to an improving U.S. economy and supply growth that has remained below the running average. However, trying to determine whether there is some correlation between roomnight demand in a state and its tourism budget can shed light on the budget’s effectiveness and contribution to lodging demand.

Florida’s growth in roomnight demand has consistently outpaced the national average over the three-year period shown. Colorado’s roomnight demand was above the national average except in 2015, and Alaska was consistently below the national average.

There are numerous variables to consider, including external economic forces like the drop in oil prices and strengthening of the U.S. dollar. However, we can hypothesize those states that implement a sustainable tourism funding model and aggressively market themselves as destinations have a higher probability of achieving more growth in demand since it is to some degree hedging against external industry fluctuations.

This analysis provides a different perspective on how state tourism dollars can affect the lodging sector. This emphasizes the importance of investing in travel and tourism to counter shocks from volatile industries such as the energy sector. Alaska significantly reduced its budget for FY 2016, which could have a negative impact on hotel performance and the tourism industry at large in the following years.

Takeaway

Measuring and illustrating the return on investment that the travel and tourism industry produces is complex since uniform data can be difficult to collect and there are numerous metrics to analyze. Thorough research and analysis can buffer against this challenge. Industry leaders, advocates and consultants need to collaborate with state tourism offices to help collect accurate data and produce meaningful metrics that can be used as industry standards.

It’s also important to realize measuring the return on investment of any travel or tourism-related project—whether it is a national marketing campaign to increase visitor attendance or development of a convention center hotel to host larger conventions—will be instrumental in winning support from state legislatures and constituents.

Overall, these analyses offer insight into the importance of the travel and tourism industry, but also show that not all return on investment metrics are made equal. It’s important to analyze more than one metric to grasp a better understanding of how tourism affects an economy and how to devise an optimum strategy. Additionally, it’s clear that a benchmark for each metric is necessary to accurately determine the effectiveness of a state’s tourism budget and advocate for additional funding. Given the size and scope of the travel and tourism industry, it deserves to be included as part of a state’s overall economic plan and funded regardless of economic downturns.